Guest article by A.V. Powell, ASA, MAAA, Founder and Chief Strategy Officer; and Molly Shaw, ASA, MAAA, Chief Actuarial Officer of A.V. Powell & Associates

Whether a start-up or campus expansion, communities are evolving to offer a wider variety of services, amenities and residence types than ever before. Increasing consumer demand for customization and variety will extend to contracts, as well. Here, A.V. Powell and Molly Shaw of A.V. Powell & Associates consider the continuing care contracts of the future, offering their predictions and recommendations for success.

Since our initiation into the continuing care space in 1979, we have heard rumors that Life Care contracts were dinosaurs and would be extinct soon.

Continuing care contracts*, previously referred to as Life Care, include those agreements sold by Life Plan Communities (LPC), aka Continuing Care Retirement Communities (CCRC), and Continuing Care at Home (CCaH) entities. These contracts offer a product similar to long-term care insurance that covers benefits or services to support changes in one’s functional status that may be temporary or permanent. In the past, these changes often resulted in a resident moving along the continuum of care, with contracts written to be location specific. In other words, monthly fees may or may not have changed when a resident moved to a different location, and were not necessarily based on the actual services they received. The continuing care concept was an innovative and unique combination of managed-care techniques with upfront funding and monthly payments to help create an affordable fee structure to cover benefit costs and risks.

When actuaries began their study of this industry in the late 1970s, there were approximately 300 entry-fee-based Life Plan Communities nationwide serving around 60,000 to 90,000 seniors. Today nearly 2,000 such communities serve more than 400,000 to 600,000 seniors—a small fraction (less than 2%) of the estimated 38 million seniors over age 70.

LPCs have typically defined themselves by the type of contract they offer. In the 1980s, the predominant contract was Type A, generally referred to as extensive or Life Care contracts. During the past four decades, we recall many conversations with marketers suggesting the Type A contract was losing favor among prospects. We and others have observed significant growth in the number of communities offering options for Type B, limited or modified contracts, and Type C, fee-for-service agreements. At first blush, this decades-long trend of offering multiple contract options might suggest that the demise of the Type A contract is imminent. However, the expansion in the type of contracts offered by LPCs does not represent the actual contract selection by prospects. To our knowledge, no one has conducted either a national or random-sample longitudinal survey to determine trends in contract selection. This would be a useful and interesting study.

So, the $64,000 question remains: What are the continuing care (Type A, B, or C) provisions that will appeal to an overwhelming majority of LPC prospects, both now and in the future?

Pondering this question is similar to pondering whether an adjustable rate or a fixed-rate mortgage is better. Most would agree that it depends on the individual’s risk aversion or tolerance, as well as the relative pricing of the products. A priori, the expected lifetime costs of healthcare and the corresponding, actuarially adequate pricing combination of an entry fee and future monthly fees are the same for all healthy individuals that would qualify for independent living admission. In other words, an individual does NOT know beforehand if a Type A (Life Care) contract will result in less lifetime cash outflows than a Type C (fee-for-service) contract. Hence, an individual cannot know, with certainty, which contract is most financially advantageous for them. This implies that most individuals should be financially indifferent to their contract selection.

However, suppose you factor in one’s risk aversion utility curve. In this case, some will prefer to “insure” themselves against uncertain financial risks, while others will be willing to accept those risks of higher-than-expected future health care utilization and costs. To actuaries, this means there is no perfect contract design—all are equally acceptable if priced on an actuarially fair basis. An anecdotal observation from our combined consulting experience: Whenever multiple contracts are offered by the same LPC and the actuarial margins show more than a 10% difference, at least 70% of prospective residents will select the contract that is in their financial favor (lowest margin).

Looking to the future, we believe there is a high growth opportunity for continuing care contracts due to the relatively low penetration among today’s target-aged seniors. Moreover, these seniors will demand more contract options to fit their perceived needs for prefunding health care. The risk-averse will select Type A contracts, while those with high risk tolerance will seek Type C or Type D (rental) contracts. Others will fall somewhere in between, opting for Type B. There is not one “right” continuing care contract for everyone. The key is to recognize and address market desires by offering variations in healthcare benefits (as evidenced by the growth of refundable contracts) and pricing them adequately with clear and transparent explanations of contract provisions.

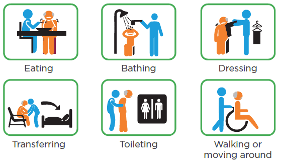

As the practice of aging in place becomes more prevalent in the future, it is likely that location will no longer trigger continuing care contract benefits. Instead, changes in an individual’s functional status or care coordination needs will be the trigger for contract benefits, similar to CCaH contracts. This means that continuing care contracts will be written so that monthly fee changes correlate with changes in the resident’s ADL or IADL status.

We believe that the most successful providers will respond by implementing risk management methods that allow them to offer all types of continuing care contracts on the same campus—including combining CCaH options with Type C contracts or unbundling Type A and B to combine with a new form of CCaH contract. For providers, this means developing admission underwriting conventions or actuarially fair fee adjustments to cover potential variations in utilization risks for an individual prospect to minimize the likelihood of adverse contract selection.

*For definitions of continuing care types, refer to this link: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Continuing_care_retirement_communities_in_the_United_States.

For more content on senior housing trends, click here.